THE SAME OLD SONG, PART TWO

Most in the business are familiar with the history of Warner Music Group, whose Warner Bros., Atlantic and Elektra labels deftly balanced art and commerce from the mid-’60s until the company’s idiotic dismantling in the mid-’90s at the hands of Bob Morgado and Michael Fuchs. But the equally significant and colorful story of CBS Records/Sony Music, WMG’s most formidable rival throughout those three decades, has yet to be told in similar detail. It’s a gripping tale that approaches a Shakespearean level of drama at certain pivotal moments. What follows is the second chapter in a recounting of the high and low points of the CBS/Sony narrative, with a focus on the individuals who shaped the company over the years, right up to this historic moment: the beginning of the Rob Stringer era.

THE RISE AND FALL OF WALTER YETNIKOFF

Clive Davis was replaced as CBS/Records Group chairman by none other than the returning Goddard Lieberson, who ran the company for the next two years, while General Counsel Walter Yetnikoff was upped to president of the international division. In 1975, Lieberson retired, Dick Asher was given the international gig and Yetnikoff was upped to president of CBS Records, marking the beginning of what would be a historic 15-year run characterized by great success fueled by extreme excess.

By the mid-’70s, cocaine had become rampant throughout the business, so much so that label staffers fell into three groups: those who did blow, those who smoked weed and those who stayed clean. “Sex and drugs and rock & roll” literally described this period of overindulgence, as office doors were kept discreetly closed, celebrity dealers—like L.A.’s Electric Larry—made regular stops at virtually every department, bindles were passed around under restaurant tables and expense accounts were full of doctored receipts. Black Rock, as industry people called the monolithic CBS building on Sixth Ave. and 52nd St., was no exception. Coke burned people out, further inflated egos and led to the demise of many.

Nonetheless, the hits kept coming throughout the decade—racked up by Springsteen, Neil Diamond, Boston, Meat Loaf, Billy Joel, Journey, Willie Nelson, James Taylor (whom Yetnikoff had poached from Warner Bros. chief Mo Ostin, who countered by poaching Paul Simon), EWF, Pink Floyd, Heart, Cheap Trick and Michael Jackson. Meanwhile, the competition between Yetnikoff and the Warner label heads ratcheted up to unprecedented levels, as the two companies mocked each other in trade ads.

Nonetheless, the hits kept coming throughout the decade—racked up by Springsteen, Neil Diamond, Boston, Meat Loaf, Billy Joel, Journey, Willie Nelson, James Taylor (whom Yetnikoff had poached from Warner Bros. chief Mo Ostin, who countered by poaching Paul Simon), EWF, Pink Floyd, Heart, Cheap Trick and Michael Jackson. Meanwhile, the competition between Yetnikoff and the Warner label heads ratcheted up to unprecedented levels, as the two companies mocked each other in trade ads.

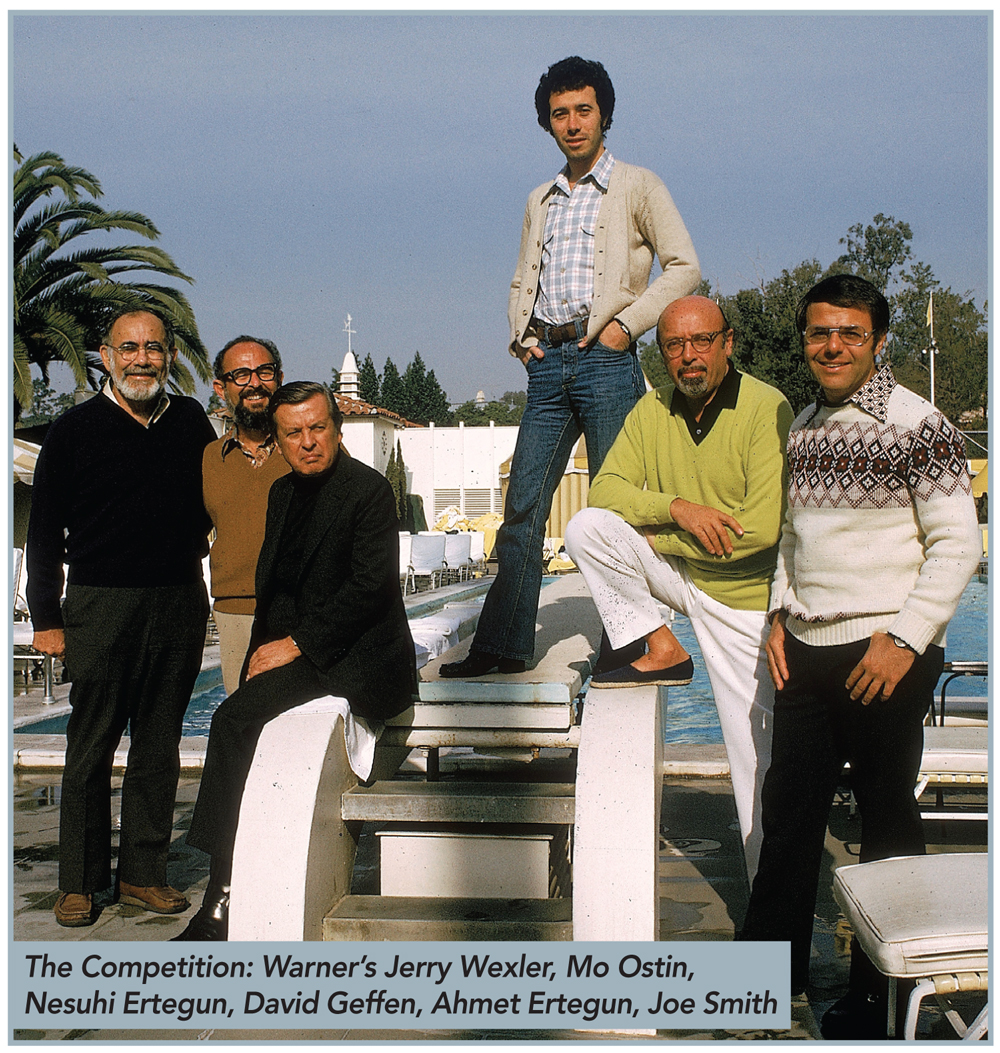

When Yetnikoff pushed what was known as “the big red button,” the CBS machine and the top indie promoters were mobilized—you could tell by songs rocketing up the airplay charts and the albums stacked to the ceiling near the checkout of every Tower Records store. Yetnikoff’s chief operators, the capable tandem of Asher and Al Teller, also knew what to do with the button; both were formidable execs, but corporate in their styles, in sharp contrast to their WMG counterparts, who consistently challenged and at times surpassed the Black Rock army. Between them, CBS and WMG controlled more than 50% of the market during those years. Many of the key players at the WMG labels were street-level entrepreneurs who’d made their bones in the rough-and-tumble world of independent distribution, with its guiding principle of never paying on time. The Erteguns, Jac Holzman, Mo Ostin, Joe Smith, Bob Krasnow, Eddie Rosenblatt, Doug Morris, Dave Glew, Mel Posner and David Geffen all came up in this independent sector, in sharp contrast to the Harvard MBAs and Ivy League lawyers at CBS Records: Clive Davis, Walter Yetnikoff, Dick Asher and Al Teller.

Columbia was headed by Bruce Lundvall from 1976 until 1981, when Al Teller was given the job; Lundvall left for Elektra in 1982. Yetnikoff and Asher were like oil and water throughout their working relationship, and Yetnikoff canned Asher in 1983. Asher would go to work at Warner Corporate before a successful run as head of PolyGram in ’85. Frank DiLeo became head of Epic promo the same year, as Jackson’s Thriller exploded, cementing a tight-knit relationship between him and MJ and elevating DiLeo’s importance in Yetnikoff’s eyes. As a result, the two became even closer. DiLeo assumed a bigger-than-life personality out of the relationships with Jackson, Yetnikoff and certain high-level independent promoters, as Jackson’s worldwide success altered the playing field. In ’84, DiLeo and Walter maneuvered Frank’s way into the gig as Jackson’s manager. He and Ray Anderson, who headed Columbia promotion, did their jobs more aggressively than any promo heads before them. But in 1986, NBC investigative reporter Brian Ross’ payola exposé derailed the indie-promo apple cart, triggering another federal investigation.

Meanwhile, Yetnikoff began to spin out of control. He felt he deserved the same treatment as Warner Communications ruler Steve Ross, and he pushed to get into the movie business, as Ross was. Then Yetnikoff started a beef with CBS corporate, which was then led by notorious cost-cutter Larry Tisch, predicated on the fact that Ross was paying his top execs far more than their modestly compensated CBS Records counterparts. These interrelated issues likely motivated Yetnikoff as he helped engineer the sale of CBS Records to Sony, which was revolutionizing the electronics business with its wildly successful Walkman personal cassette players. The deal was closed for the then-hefty price of $2 billion in 1988. Two years later, Yetnikoff again pushed Sony into purchasing Columbia Pictures for $3.4b, much of the booty going to majority owner Coca-Cola. He also helped bring in

Peter Guber and Jon Peters to run the company, which was renamed Sony Pictures Entertainment. Post-sale, Mickey Schulhof entered the picture as chairman of Sony America, giving him over-sight of film, TV and music. Throughout this period, Yetnikoff was pushing people’s buttons and burning bridges in every sector, and his opponents began to smell blood in the water.

Meanwhile, Yetnikoff began to spin out of control. He felt he deserved the same treatment as Warner Communications ruler Steve Ross, and he pushed to get into the movie business, as Ross was. Then Yetnikoff started a beef with CBS corporate, which was then led by notorious cost-cutter Larry Tisch, predicated on the fact that Ross was paying his top execs far more than their modestly compensated CBS Records counterparts. These interrelated issues likely motivated Yetnikoff as he helped engineer the sale of CBS Records to Sony, which was revolutionizing the electronics business with its wildly successful Walkman personal cassette players. The deal was closed for the then-hefty price of $2 billion in 1988. Two years later, Yetnikoff again pushed Sony into purchasing Columbia Pictures for $3.4b, much of the booty going to majority owner Coca-Cola. He also helped bring in

Peter Guber and Jon Peters to run the company, which was renamed Sony Pictures Entertainment. Post-sale, Mickey Schulhof entered the picture as chairman of Sony America, giving him over-sight of film, TV and music. Throughout this period, Yetnikoff was pushing people’s buttons and burning bridges in every sector, and his opponents began to smell blood in the water.

Teller was honored by the TJ Martell Foundation in 1988, with Joe Smith serving as roast-master, just before Yetnikoff fired Teller as President of the Records Group, replacing him with successful artist manager and major player Tommy Mottola. Many of those who attended the ceremony knew that night that Teller was on the way out and Mottola was about to take his throne. Teller went to MCA, succeeding Irving Azoff. Attorney Allen Grubman repped Mottola when he did his deal with Yetnikoff, with whom he had a “very, very” close relationship—it was rumored that Yetnikoff paid Grubman seven figures a year as a consultant. Grubman was the ultimate insider/dealmaker and consigliere to the power players; his client roster included Geffen Records, Davis, Irving Azoff, Chris Blackwell, Chris Wright, Clive Calder, Springsteen, Billy Joel, Madonna, Bon Jovi, John Mellencamp, Hall & Oates and U2. Thus began a seismic shift in which the corporate MBAs and lawyers at Sony Music were replaced by street-smart execs like those at the Warner labels, as Grubman moved pieces around the chessboard.

Teller was honored by the TJ Martell Foundation in 1988, with Joe Smith serving as roast-master, just before Yetnikoff fired Teller as President of the Records Group, replacing him with successful artist manager and major player Tommy Mottola. Many of those who attended the ceremony knew that night that Teller was on the way out and Mottola was about to take his throne. Teller went to MCA, succeeding Irving Azoff. Attorney Allen Grubman repped Mottola when he did his deal with Yetnikoff, with whom he had a “very, very” close relationship—it was rumored that Yetnikoff paid Grubman seven figures a year as a consultant. Grubman was the ultimate insider/dealmaker and consigliere to the power players; his client roster included Geffen Records, Davis, Irving Azoff, Chris Blackwell, Chris Wright, Clive Calder, Springsteen, Billy Joel, Madonna, Bon Jovi, John Mellencamp, Hall & Oates and U2. Thus began a seismic shift in which the corporate MBAs and lawyers at Sony Music were replaced by street-smart execs like those at the Warner labels, as Grubman moved pieces around the chessboard.

Privacy Policy - Terms and Conditions

| Site Powered by | |